“The Telephone Conversation by Wole Soyinka” is a satirical poem penned in 1963, that addresses the issue of racism. It unfolds the narrative of a telephone call between the speaker, a black individual, and a landlady negotiating an apartment rental. Initially amiable, the landlady’s demeanour takes a sharp turn when she discovers the speaker’s African identity, prompting intrusive inquiries about the shade of the speaker’s skin. In a witty rejoinder, the speaker adeptly ridicules the landlady’s ignorance and bias, skillfully highlighting the dehumanizing nature of categorising individuals based on their skin colour. Thus, “The Telephone Conversation by Wole Soyinka” serves as a poignant exploration of societal prejudices.

Table of Contents

The Telephone Conversation by Wole Soyinka

The price seemed reasonable, location

Indifferent. The landlady swore she lived

Off premises. Nothing remained

But self-confession. “Madam,” I warned,

“I hate a wasted journey–I am African.”

Silence. Silenced transmission of

Pressurized good-breeding. Voice, when it came,

Lipstick coated, long gold-rolled

Cigarette-holder pipped. Caught I was foully.

“HOW DARK?” . . . I had not misheard . . . “ARE YOU LIGHT

OR VERY DARK?” Button B, Button A.* Stench

Of rancid breath of public hide-and-speak.

Red booth. Red pillar box. Red double-tiered

Omnibus squelching tar. It was real! Shamed

By ill-mannered silence, surrender

Pushed dumbfounded to beg simplification.

Considerate she was, varying the emphasis–

“ARE YOU DARK? OR VERY LIGHT?” Revelation came.

“You mean–like plain or milk chocolate?”

Her assent was clinical, crushing in its light

Impersonality. Rapidly, wave-length adjusted,

I chose. “West African sepia”–and as afterthought,

“Down in my passport.” Silence for spectroscopic

Flight of fancy, till truthfulness clanged her accent

Hard on the mouthpiece. “WHAT’S THAT?” conceding

“DON’T KNOW WHAT THAT IS.” “Like brunette.”

“THAT’S DARK, ISN’T IT?” “Not altogether.

Facially, I am brunette, but, madam, you should see

The rest of me. Palm of my hand, soles of my feet

Are a peroxide blond. Friction, caused–

Foolishly, madam–by sitting down, has turned

My bottom raven black–One moment, madam!”–sensing

Her receiver rearing on the thunderclap

About my ears–“Madam,” I pleaded, “wouldn’t you rather

See for yourself?”

Summary

The apartment seemed like a good deal, and the location was okay. The landlady assured me that she didn’t live in the building. The only thing left was to share something important about myself. So, I told her, “Ma’am, I don’t want to waste a trip. Just so you know, I’m black.”

There was silence on the phone. In that silence, I could feel the tension between the landlady’s prejudices and her manners. When she finally spoke, she sounded like someone who might wear a lot of lipstick and have a long, gold cigarette holder. Now, I was in an awkward spot. “How dark are you?” she asked bluntly. It took a moment to realize I hadn’t misheard her. She repeated, “Are you light-skinned or very dark-skinned?” It was like choosing between Button A and Button B on a phone booth: to make a call or get a refund. I could smell her bad breath hidden behind her polite words.

Taking in my surroundings – a red phone booth, a red mailbox, a red double-decker bus – I realized this kind of thing actually happens! Feeling embarrassed by my silence, I reluctantly asked for clarification, utterly confused and shocked. She kindly rephrased the question: “Are you dark-skinned or very light?” Finally, it made sense. I replied, “Are you asking if my skin is the colour of regular chocolate or milk chocolate?” Her confirmation was cold and formal, devastating in how thoughtless and impersonal she sounded. Changing my approach, I quickly chose an answer: “My skin colour is West African sepia.” Then, as an afterthought, I added, “at least it is in my passport.” Silence followed as she imagined the possible colours I might be referring to. But her true feelings emerged, and she spoke harshly into the phone.

“What is that?” she asked, admitting, “I don’t know what that is.” “It’s a brunette color,” I told her. “That’s pretty dark, isn’t it?” she asked. “Not entirely,” I replied. “My face is brunette, but you should see the rest of my body, ma’am. My palms and the soles of my feet are the color of bleached blond hair. Unfortunately, ma’am, all the friction from sitting down has made my butt as black as a raven. Wait, hang on for a moment ma’am!” I said, sensing she was about to hang up. “Ma’am,” I pleaded, “don’t you want to see for yourself?”

Analysis

This analysis will help you remember the complexity of human identity, the absurdity of racial categorization, and the ongoing fight for equality.

Beyond “Dark” or “Light”

Wole Soyinka’s “Telephone Conversation” isn’t a casual chat; it’s a satirical scalpel, dissecting the ugly abscess of racism through a seemingly mundane phone call. The conversation, ostensibly about renting an apartment, quickly devolves into a stark display of prejudice, exposing its insidious nature through a powerful dialogue of quotes.

The Insidious Creep of Bias

The poem opens with hopeful inquiries about “a flat to let,” suggesting a sense of normalcy. But when the speaker declares, “I am African,” the tone shifts. The landlady’s casual “nice” masks a sudden tension, as her reply, “Which part?” reeks of thinly veiled prejudice. She seeks to categorize, to fit the speaker into a preconceived box before considering him as an individual.

Colour-Coded Humanity

The crux of the conversation revolves around a grotesque obsession with skin colour. The landlady’s repeated, insistent “Are you dark? Or very light?” betrays her warped worldview, where a person’s worth is reduced to melanin levels. The speaker’s retort, “Madam, I hate a wasted journey—I am African,” is both dignified and defiant, refusing to play into her discriminatory game.

Beyond the Binary

The landlady’s simplistic binary of “dark” and “light” is shattered by the speaker’s nuanced response: “Like brunette, that got us sunburnt.” He subverts her expectations, revealing the absurdity of racial categorization in the face of human complexity. His identity cannot be contained in such simplistic terms.

Humour as Resistance

Despite the ugliness of the situation, Soyinka employs wit as a weapon. The speaker’s dry commentary on “public hide-and-speak,” referring to the hidden nature of prejudice, stings with truth. His witty comparison of himself to a leopard, “But not those with fangs and claws,” disarms the landlady with its unexpected humour, while subtly pointing out the absurdity of her fear.

A Conversation Across the Divide

Ultimately, the poem leaves us with a chilling question: is true communication even possible across such a vast chasm of prejudice? The speaker’s final, resigned acceptance, “Never mind,” speaks volumes. He recognizes the futility of the conversation, the impossibility of bridging the gap with words alone.

💡“Telephone Conversation” is more than just a poem about a rental inquiry; it’s a powerful indictment of racism and its insidious effects. Through the stark contrast between characters and their biting quotes, Soyinka forces us to confront the ugliness of prejudice and the enduring struggle for true human connection across racial divides. It’s a call to action, not just to dismantle discriminatory policies, but to dismantle the discriminatory thinking that fuels them.

Literary Devices Used

- Free Verse: The poem’s lack of formal structure mirrors the chaotic and unpredictable nature of the conversation. It allows for sudden shifts in tone and emphasis, reflecting the speaker’s frustration and the landlady’s bigotry.

- Irony: The landlady’s questions about the speaker’s suitability for the apartment become increasingly absurd, highlighting the irony of her prejudice. The humour, however, is dark and tinged with anger.

- Repetition: The landlady’s obsessive repetition of “dark” underscores the poem’s central theme. It becomes a mantra of exclusion, a stark reminder of the barriers faced by people of colour.

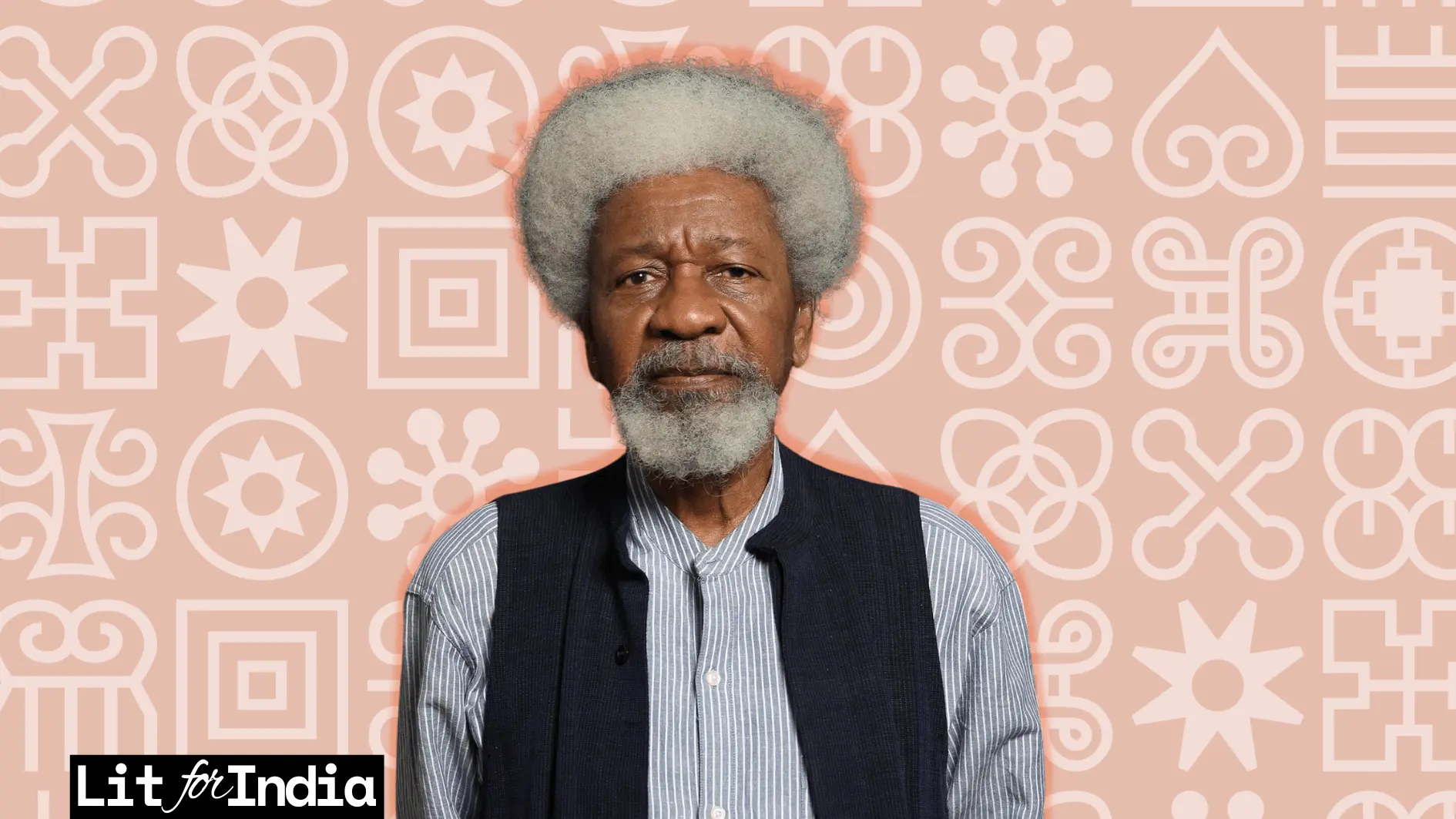

About the Author

Wole Soyinka, a towering figure in African literature, is a Nigerian playwright and poet renowned for his impactful contributions to the literary world. Awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986, Soyinka’s work delves into complex themes such as oppression, tyranny, and the struggle for independence in Nigeria.

With an impressive repertoire comprising 29 plays, two novels, and a diverse collection of memoirs, essays, and poetry, Soyinka’s literary prowess reflects his deep engagement with socio-political issues. His writing, often characterized by a keen sense of social criticism, extends beyond the boundaries of the literary realm, addressing the broader challenges faced by society.

Soyinka’s enduring influence is marked not only by his distinguished body of work but also by his commitment to using literature as a powerful tool for social commentary and change.

Conclusion

While “Telephone Conversation” ends on a muted note, it lingers in the mind, a persistent hum that refuses to be ignored. The Telephone Conversation by Wole Soyinka doesn’t offer easy answers, but it compels us to listen, to confront the uncomfortable truths it holds, and to strive for a world where skin colour isn’t the first line of dialogue, but one line among many that paint the beautiful, intricate tapestry of our shared humanity.